- Home

- Graham Lironi

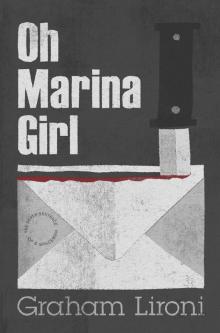

Oh Marina Girl

Oh Marina Girl Read online

Praise for Oh Marina Girl

“Oh Marina Girl has all the makings of a cult classic… in fact, I haven’t enjoyed reading a novel as much as this for some time. It’s a book you could become obsessed with. This is too good to be kept a secret.” Alistair Braidwood, Scots WhayHae

“Very mysterious and clever… a very nicely crafted story. Twisty and exciting.” Bookcunt

Praise for Graham Lironi’s previous books

“An intelligent, original and disturbing new voice in Scottish fiction.” A L Kennedy

“A haunting and original piece of work, a cult book in the making.” Herald

“The new bad boy of Scottish fiction is misbehaving very well indeed.… has the pace, intensity and cultural referencing of a literary Pulp Fiction.” The List

“A slick unfussy writer who keeps things moving to their sticky end.” Sunday Herald

“Graham Lironi is for real.” Scotsman

“Written in a taut and clinically precise prose… a writer with a truly promising future.” Ann Donald

“A disturbing, challenging and often bizarre story… which challenges its readership concerning truth and the deeper meaning and purpose of life itself… this book is worth seeking out.” Life & Work

“A powerful book… A twisting tale of teenage sex, lies and hillwalking… The reader is left to answer the question, ‘Did this really happen?’ An excellent first novel.” East Lothian Life

Oh Marina Girl

the death sentence of a spaceman

Graham Lironi

For my family,

At long last, it spirals out now.

‘In the beginning was the word. Its letters were a string of amino acids that spelt the genesis of life. The letters multiplied enormously and now come in whole libraries that we pass on to our descendants.’

Paul Peter Piech

Contents

Praise for Oh Marina Girl

Oh Marina Girl

part one

i am not he

chapter one

the spaceman

chapter two

verbatim

chapter three

a tight spot

chapter four

alphabetti spaghetti

chapter five

cross-reference

chapter six

crosswords

chapter seven

filling empty space

part two

atone him

chapter eight

flesh out

chapter nine

an envelope without an address

chapter ten

suicide note

chapter eleven

forgery

part three

thai omen

chapter twelve

the front page (1)

chapter thirteen

the price of free speech

chapter fourteen

expulsion from in a robot

chapter fifteen

something more than words

chapter sixteen

never the twain shall meet

chapter seventeen

the front page (2)

chapter eighteen

letter bomb

part four

mine oath

chapter nineteen

spell it out

part five

i’m on heat

chapter twenty

the present tense

chapter twenty-one

her word against mine

part six

a tin home

chapter twenty-two

character assassination

chapter twenty-three

a death sentence

chapter twenty-four

the footnote

chapter twenty-five

a new chapter

Acknowledgement

Copyright

part one

i am not he

chapter one

the spaceman

That fateful morning began like any other weekday of the past decade: I rolled out of bed, gulped down cornflakes, showered, shaved, shit, caught the number 44 bus into work, scanned the paper en route, squeezed into the crowded lift (despite my claustrophobia) to the first floor and, unable to resist the temptation, before I even removed my coat and hat, stopped and glanced at the translucent purple paperweight pinning down the pile of letters on my desk.

The letters hadn’t always drowned me in apathy; there was a time when they’d stirred me with enthusiasm — but that was long ago when I was a fresh-faced raw recruit fired with ambition. Possessed with a shiny new evangelical zeal, I’d fancied I was embarking on a moral crusade that would expose the city’s corrupt underbelly. My zeal had long since been buried beneath a thickening layer of apathy and I’d become resigned to watching the spread of the corruption all around me.

Apathy was invariably the cause of any occasional mistake made by myself; but I was fortunate in that I’d made only one serious error in my career to date when I’d unintentionally hit the space bar when writing about a therapist so that instead of the sentence reading, ‘Therapist John McDonald...’, it read, ‘The rapist John McDonald...’.

The newspaper, a broadsheet, had national ambitions, but its circulation was confined largely to the city where it was produced. Its local news coverage outweighed its national news coverage which outweighed its international news coverage. The letters, I knew before opening them, would reflect this weighting of local, national and international concerns.

The exception to this rule of parochialism occurred periodically with the onset of exceptional circumstances, such as those prevailing at present, with Britain having just committed itself to participation in the resolution of a bloody conflict between opposing ethnic groups in central Europe; a commitment made on the basis of the laudable humanitarian principle that it is unacceptable for us as a nation to sit idly by whilst an undemocratic regime headed by a bloodthirsty tyrant repeatedly ignores all United Nations appeals to reason and proceeds to invade its bordering nation’s territory to carry out a systematic slaughter of its neighbours in an attempt to render extinct an entire race.

Newspapers relish such exceptional circumstances: publishers rejoice in the sudden surge in circulation figures; journalists revel in the opportunity to express their moral indignation and the sense of self-worth that reporting such events gives them. I am exceptional in my distinct lack of enthusiasm.

You see, the day before’s front page, and several inside pages, had been devoted to an examination of the ramifications of the announcement of Britain’s involvement in the escalating international crisis and I knew that, for the foreseeable future, whilst the quantity of letters landing on my desk would multiply, their diversity would contract into two opposing camps: those from readers writing to express their support for Britain’s intervention and those opposed to it, so that, whilst journalists discovered their raison d’être, I discovered new peaks of monotony.

Of course, none of the letters were addressed to me personally. Rather, they were addressed to ‘the letters page’ and dumped on my desk for me to open.

This was a process I wouldn’t begin until I’d removed my raincoat and jacket, taken off my homburg, hung up my umbrella and ventured into the kitchen to make myself a cup of peppermint tea.

That morning, I found myself occupying the space between the parallel universes of a pair of overripe bottle-blonde cultural commentators

— engrossed in a voluble conversation on remedies for period pain — and a pair of teenage sports correspondents, engrossed in an equally voluble conversation about the implications of the result of the previous evening’s match on the eventual outcome of the league, and how it had turned on a woeful performance by the referee who had blown his whistle for an offside that clearly wasn’t but failed to blow it for a penalty that clearly was. Obviously their favoured team had lost.

Both the cultural commentators and the ‘sports’ (which in Glasgow was a term synonymous with ‘football’) correspondents appeared oblivious to events outwith their own particular areas of expertise; such as the fact that we were on the brink of entering into a war.

‘Morning.’

Both parallel conversations stopped abruptly and I looked up from stirring my tea to see the occupants of the kitchen waiting for me to respond.

‘Morning,’ I obliged.

‘How’s the missus?’ asked Kirsty Baird, the more buxom of the blondes.

‘Fine,’ I lied, ‘she’s fine.’

This had been my standard response since the first morning I returned to work a few days after receiving Lisa’s first and last letter. It was an automatic defence mechanism designed to deflect from divulging the truth; a ruse deployed out of recognition that the truth was not always the desired response in matters of everyday social etiquette.

Lisa had never been my missus. She’d insisted on a Catholic wedding ceremony and I’d insisted on a registrar office until the subject was consigned to the burgeoning list of taboos spread out between us, all interlinked by faith and faithlessness, separating us by its immovable bulk.

No, Lisa had never been my missus. She was one of my two misses — the other was Will — and the space left by their absence defined me.

I decided it was time I started slitting some envelopes, an everyday function which, over years of monotonous repetition, had become endowed with the solemnity of a sacramental rite. I performed this ritual with a letter opener that masqueraded as a traditional Highland knife, or skean dhu. Lisa had given it to me long ago when I’d first landed this job.

Nobody could slit an envelope like me. I’d perfected it into an art form, gutting it with one swift slash.

But before I’d start slitting, I’d put on my tortoiseshell specs, after wiping the lenses with a hankie to which I’d applied a sliver of saliva, boot up the computer to start printing out the e-mails (I refuse to ruin what’s left of my failing eyesight by squinting at a reflective screen), shuffle and staple the faxes and rifle through the envelopes in the hope of discovering an exotic postmark. By this time my tea will have cooled sufficiently to allow me my first slurp.

I never start to read the letters until I’ve disembowelled all the envelopes. When this is done, I’ll open the letters out, place them in a neat pile and contemplate them, sipping my tea. There was a time when my taste buds had savoured the peppermint prospect of what priceless pearls of wisdom the pile before me might contain, but that was long ago and the piles had long since lost their flavour.

Only once I’d drained my cup did I buckle down to the task of reading.

It was a task within which I’d immerse myself until noon, at which time I’d pick up my umbrella, don my raincoat and homburg, take the lift down to the ground floor and stroll to the Mitchell Library to while away an hour browsing amongst books on calligraphy.

Given the monotony of my job, it was perhaps inevitable that I should become a self-taught, and sometimes subconscious, graphologist. Scrutinising the endless flow of scribbles lassoed by extravagant loops, and the indecipherable signatures, to construct my personality profile of various letter writers.

But I’d recently become intrigued by the spaces between the words as much as the words themselves. You see, I began to notice some time ago, and I’ve been fascinated by it since, that, however different our handwriting might be, the gap we leave between our words is always consistent. We do this automatically — or at least we did — because, now that I’ve pointed it out to you, you probably can’t help but be conscious of the gap you leave.

It’s not unusual for me to finish a letter only to realise that I’ve immediately forgotten what I’ve just read. The clearest example of this I can recall was when I was so disturbed by the calligraphy of a particular letter that I became convinced that its author was a potential murderer, only to discover, after having read it for the third time, that the letter was, in fact, a confession to matricide.

But, from the very start, the content of one of this morning’s letters grabbed my full attention — perhaps because of its anonymity (literally — there was no signature; and calligraphically — it was written on bog-standard foolscap with a bog-standard blue biro). Yet there was also something familiar about the handwriting which I couldn’t quite pinpoint.

When I finished it I glanced over at my colleagues to check that they were engrossed in their own screens or conversations, then refolded it and slipped it into the breast pocket of my stiff-collared, white Bri-Nylon shirt.

I attempted to resume my letter reading, but no matter how extravagant the loops and hoops, how intriguing the signature, it was the letter burning through my shirt pocket that I was rereading.

Apart from the handwriting, one other particular aspect of the letter perplexed me all morning — though I realised it would only be me for whom it was a puzzle. Then, when the umpteenth trawl through my bin failed to find a disembowelled and discarded matching envelope stamped with an identifiable postmark I belatedly perceived to be of paramount importance, a possible explanation to the puzzle finally dawned on me.

I gasped, cursed myself under my breath, ran to the library an hour earlier than usual, forgetting my umbrella in my haste to confirm the solution to the puzzle, causing some consternation amongst those of my colleagues who set their watches by the precision of the hitherto meticulous routine I had just abandoned with such uncharacteristic impetuousness.

I suppose it would be easier for you to understand my actions if I explained the content of the letter to you. In fact, I can do better than that — I can reproduce it for you verbatim:

Intolerance will not be tolerated.

Following the publication of his letter in yesterday’s paper, I have taken hostage Ian Thome. I will slit his throat unless you publish this letter, unedited, on the front page of tomorrow morning’s paper and promise never again to publish such a misguided defence of pernicious propaganda. Failure to do so will result in your own capture and execution.

Do not contact the police. Do take this threat seriously. Remember what happened to Craig Liddell.

Whilst this verbatim reproduction of the letter will no doubt give you some inkling of why it received my full and horrified attention, since you are presently unaware of the context within which it was written and the people referred to in it, it will probably make little sense to you. Nor will it be clear to you what, specifically, puzzled me.

chapter two

verbatim

Firstly, let me tell you a little about Craig Liddell.

Although I had no more than a passing acquaintance with Liddell, several of my colleagues had known him well — the city centre is sufficiently condensed to enable the more sociable members of the fraternity of those who earn their daily bread from the written word to congregate in cliques outwith office hours.

I was on the periphery of this incestuous circle — partly through choice (over recent years it had become infested with a plague of PR parasites who had infiltrated it with the objective of buying drinks for the circle’s other members with their paymaster’s moolah and bending the ears of the circle’s other members with their paymaster’s propaganda in the hope that it would subsequently appear in print the following day. More often than not it did, but I preferred to restrict my relations with such practitioners of the dark arts to a strictly professional basis, uncomf

ortable with the notion that the cultivation of friendships could only compromise my precious editorial integrity), partly through my lowly status as a letters page editor (it was not a position overburdened with kudos — which suited me fine since it meant that I didn’t have succeeding generations of overeager graduates fighting amongst themselves to replace me, unwittingly driving down the potential remuneration package through their competitive zeal), but mostly because of my unsociable preference for spending my lunch hour browsing amongst books of calligraphy in the Mitchell Library rather than contributing to the gossip masquerading as wheeling and dealing that takes place over extended lunch time G&Ts at the Space Bar (a name that ensured that I would never be permitted to forget my unfortunate faux pas).

Liddell had been a book reviewer on a lifestyle magazine, which made him an integral member of the incestuous circle. He had the kudos I lacked, the sociability I lacked and the ability to cultivate friendships with the PR parasites without allowing them to compromise his integrity, which I lacked.

If that sounds like I envied him then that’s because I did — but I certainly don’t envy what happened to him.

Liddell had a reputation amongst his fellow critics for being acerbic but fair, which meant that he had a reputation amongst authors for being scathing and unfair (though this grudge was seldom, if ever, shared by the author’s own PR parasites who, having already written off any given book, and with one eye already on the next launch for the next author on a burgeoning list, without exception confided to Liddell that, strictly off the record, they concurred with his criticisms).

It was only a month since Liddell had been killed and the reactions to his murder had dominated the letters page for days afterwards. My paper, and its competitors, had reported and analysed the incident in depth. This had, after all, been regarded by those members of the incestuous circle as an attack on one of its own; an attack on the very principle that allowed them to tell themselves that they were employed in a noble profession; an attack on what gave a purpose to their lives.

Oh Marina Girl

Oh Marina Girl